By Rachel Lamb . 24/07/2017 · 9 Minute read

Most people will experience a surgical procedure at some point in their lives and, if you work in an operating theatre-based role, you’ll be used to helping them get through it. Surgery has become so common-place within our society that people will opt for a surgical procedure for purely cosmetic reasons, but go back 200 years and you’d be looking at a very different story…

Surgery in the nineteenth century

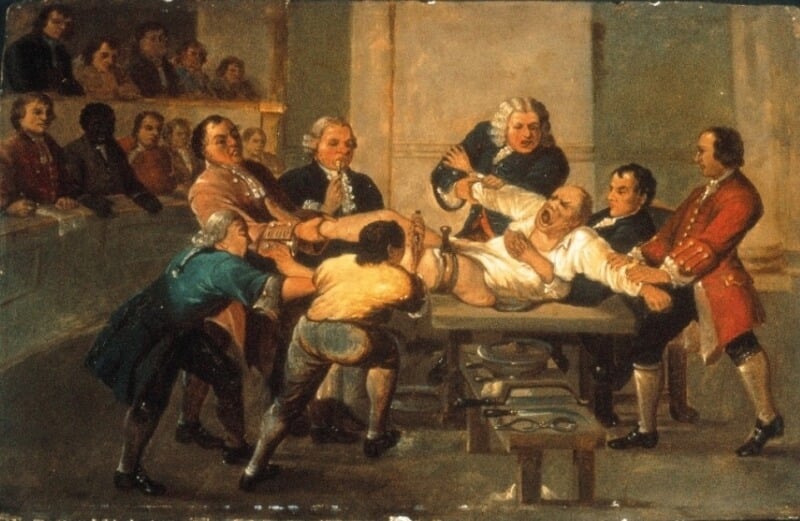

In the early to mid-nineteenth century, surgery was a gruesome, traumatic experience that even the bravest of people avoided like the plague. To start with, there was no anaesthetic – it simply hadn’t been invented yet – which meant that patients were fully conscious when being operated on. Imagine having your leg amputated without any form of pain relief? People were so terrified of going through surgery that allowing their injuries/diseases to fester was the preferable choice.

Now imagine experiencing the worst pain of your entire life…in front of an audience of 150 scholars and students. Patients would undergo surgery with hundreds of onlookers studying (and often enjoying) their horrific ordeal. The term ‘operating theatre’ makes perfect sense now!

Roughly 25% of patients eventually died from post-surgical infection (which is no surprise as the same operating theatres and tables were also used for examining dead bodies).

The discovery of ether as an anaesthetic

By the mid-nineteenth century, a chemical substance called ether was being used as a recreational high in the United States. ‘Ether frolics’ (parties) were regularly hosted by the aristocracy, and it was during one particular frolic in the town of Jefferson where a medical scholar named Crawford Long discovered the connection between inhaling ether and the prevention of pain. An attendee took a heavy fall but, due to his inhalation of ether, showed no indication of pain. Long never published his findings as he wanted to make sure his theory was correct.

In 1846, an American Dentist named William Morton claimed to be the first person to successfully use ether as an anaesthetic when he extracted a tooth with no pain. Many others were also claiming the same achievement though, so Morton spent much of his life fighting for this title.

Following Morton’s painless surgical procedure, the use of ether in the operating theatre became hugely popular. Robert Liston, a famously skilled Scottish surgeon, was the first person in Britain to amputate a limb using ether.

Ether did have some drawbacks – it made patients throw up violently and was also explosive, which made operating near lamps and fires very difficult.

Pain-relief using laughing gas

Nitrous oxide (or laughing gas), was discovered for its anaesthetic properties by a teenage chemist named Humphry Davy. Davy was experimenting with new gases to inhale and found that nitrous oxide not only caused great euphoria but significant pain relief. Sadly, Davy’s findings were not acted upon and he kept them largely to himself and his friends for recreational use. It wasn’t until thirty years or so later that laughing gas was introduced for the medical industry.

It is worth noting Horace Wells here, a dentist from America who cared deeply about reducing pain for his patients during dental extractions. Wells had witnessed demonstrations of nitrous oxide and wanted to trial its effect as an anaesthetic. He was so dedicated to his cause that he even had one of his own teeth removed under the influence of laughing gas – he felt no discomfort. However, when he showcased his findings to an audience of Harvard medical students, the student he was performing an extraction on cried out and Wells was dismissed with shouts of ‘humbug!’. Wells was disgraced but continued trialling ether and chloroform away from the public eye, becoming addicted to inhaling the latter. Under its influence, Wells threw sulfuric acid over two people and was sent to prison. Once sober, ashamed and devastated by his actions, he committed suicide in 1848.

Picture of Horace Wells

Sadly, just twelve days before his death and unknown to him, Wells was honoured by the Parisian Medical Society as the first to discover and perform operations without pain.

The introduction of Chloroform

Most people know chloroform as that drug used in lots of movies for knocking someone out. However, chloroform wasn’t recognised for this property until an old colleague of Robert Liston, a Scottish Obstetrician named James Simpson, began experimenting with chemicals to use as a new anaesthetic. Simpson was aware of ether’s drawbacks and wanted to introduce a substance with the same anaesthetic advantages and less of the disadvantages. When he came across chloroform in 1847, he inhaled it and was knocked out cold.

Simpson later went on to use chloroform on women in labour, which caused much controversy in both the religious and medical worlds. However, this dispute was closed when Queen Victoria swore by chloroform after it was administered it to her for the birth of Prince Leopold in 1853 and Princess Beatrice in 1857.

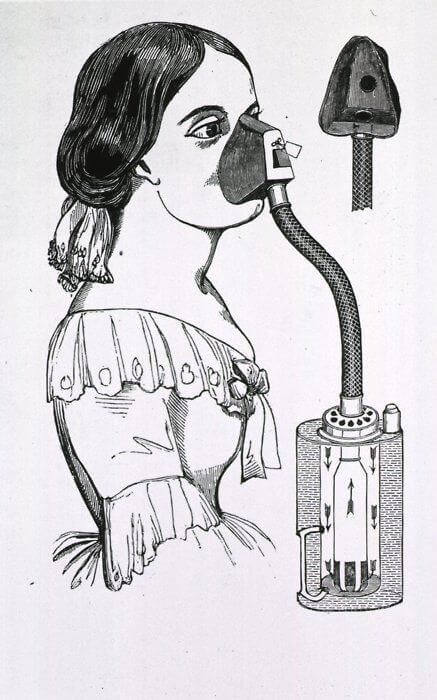

Chloroform inhaler, created by Dr John Snow

Chloroform did however have its first fatality when used on fifteen-year-old Hannah Greener, who only required surgery for the removal of an ingrowing toenail in January of 1848. Greener’s death is still widely debated but many now believe that chloroform causes cardiac dysrhythmia, which may have led to her death.

The search for a local anaesthetic

The death of Hannah Greener highlighted a problem with anaesthesia – some procedures only required the numbing of a certain body part, and not for the patient to be completely unconscious. The hunt for a local anaesthetic was on and these were the results:

1860: Albert Niemann, a German chemist, created a substance he called ‘Cocaine’ by distilling the leaves of the coca plant. Some doctors trialled this by performing their own surgery under cocaine’s influence! Cocaine proved to have analgesic properties but was extremely addictive and resulted in poor brain function. This made publishing findings on the drug very difficult (because they rarely made sense).

1905: Novocaine (Procaine) was produced 45 years after cocaine by Alfred Einhorn. He initially developed it as an anaesthetic for amputations but it was adopted for pain relief in dentistry.

1938: Explorer, Richard Gill, journeyed to retrieve a drug used by the Amazonian Indians called Curare (pronounced kyoo-rahr-ee). Gill brought the drug back to America but it was largely ignored in the medical profession until shortly before Gill’s death in 1958.

Curare, a liquid, was a step away from the traditional practice of gas/chemical inhalation. It was directly administered into the body and worked by blocking the transmission between nerves and muscles, causing the muscles to completely relax. This was extremely beneficial for surgeons as it allowed them to perform abdominal surgeries or tracheal intubation.

1964: Ketamine, a derivative of PCP, was introduced. It was known to cause twitching, retching, vomiting, throat spasms and tremoring. It also caused delusional, violent and self-destructive behaviour. Drug companies deemed Ketamine safe for analgesic use on humans following trials on prison inmates. Ketalar (the brand name for Ketamine) became available via prescription in 1966 and was widely used on children, and soldiers during the Viet Nam War. Ketamine is still used in emergencies, but with sedatives to prevent side-effects.

The ‘perfect anaesthetic’ myth

These days, we know that the perfect anaesthetic doesn’t exist. It’s far safer and more effective to use a cocktail of different substances than to stick with one large dose of a single anaesthetic. Today, we use over 100 analgesic drugs during surgical procedures and advancements in technology means we have the power to closely monitor every bodily function throughout an operation.

Find out more and apply for Your World Healthcare's Operating Theatres jobs by clicking here.

Do you have something to add? Don’t be shy, tell us your thoughts by commenting below!